SOKA GAKKAI TIMELINE

1960: Daisaku Ikeda was inaugurated as third Soka Gakkai president. As a first step to transform the Soka Gakkai into a global movement, Ikeda visited the U.S., Canada and Brazil. He established Soka Gakkai of America.

1966: President Ikeda visited the United States and established six new General Chapters.

1966: The Group changed its name to NSA, Nichiren Shoshu Academy (NSA).

1967: The first temples in the U.S. opened: Honseiji Temple in Hawaii and Myoho-ji Temple in Etiwanda, California.

1968: NSA began to grow rapidly in the counter culture with its message of personal revolution and world peace.

1972: Myosenji Temple opened in Washington, D.C. George M. Williams was appointed General Director of NSA.

1972: NS members donated $100,000,000 toward construction of the Sho-Hondo Grand Main Nichiren Shoshu Temple and attended the completion ceremony at the Head Temple Taiseki-ji at the foot of Mt. Fuji where Nichiren Daishonin’s Dai Gohonzon was enshrined.

1972: Ikeda met for the first time with British historian Arnold J. Toynbee at his home in London; the two collaborated on a dialogue later published as Choose Life.

1975: Ikeda met with U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in Washington D.C.

1976 (July 3-5): The NSA Bicentennial Convention (Thirteenth General Meeting) was held in New York City ith the theme “Toward the Dawn of World Peace.”

1979: Daisaku Ikeda was forced to resign as president of Soka Gakkai in Japan following a dispute with the priesthood of Nichiren Shoshu but remained president of Soka Gakkai International (SGI).

1980: The sixty-seventh Nichiren Shoshu High Priest, Nikken Shonin, enshrined a Joju Gohonzon at the World Culture Center in Santa Monica “for the accomplishment of the great desire for world peace and kosen-rufu” (converting the majority of the world to Nichiren Shoshu Buddhism).

1981: President Daisaku Ikeda made three trips to the United States.

1981: The First Grand World Peace Youth Culture Festival was held in Chicago with President Ikeda and High Priest Nikken Shonin in attendance.

1982: 15,000 SGI-USA members travelled to Japan for the Second World Peace Culture Festival.

1991: The Nichiren Shoshu Priesthood, after years of conflict with Soka Gakkai leadership, excommunicated 11,000,000 Soka Gakkai members worldwide.

1993: The Boston Research Center for the twenty-first century was opened in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It was renamed the Ikeda Center for Peace, Learning, and Dialogue in 2009.

1993: SGI-USA began conferring Gohonzons to members without participation by the Nichiren Shoshu clergy.

1995: The SGI Charter was approved by the SGI Board of Directors.

2000: Middleway Press was founded by SGI-USA.

2001: Soka University was founded in Aliso Viejo, California.

2002: Daisaku Ikeda began issuing public proposals for addressing world problems.

2006: Minoru Harada was inaugurated as sixth Soka Gakkai president.

2008: The Washington D.C. Culture of Peace Resource Center was opened on Massachusetts Avenue in the heart of Embassy Row.

2010: The Decade of Nuclear Abolition was announced.

2015: The first White House Conference of Buddhist Leaders was held.

2016: As of 2016, Soka Gakkai International claimed 11,000,000 members in 192 countries around the world,  with over 300,000 in the U.S.

with over 300,000 in the U.S.

2023 (November 15): Ikeda Daisaku died.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Nichiren Buddhism was founded in Japan in 1279 by Nichiren Daishonin (1222-1282). It continued as a small Buddhist sect, Nichiren Shoshu, in Japan until two friends, Tsunesaburo Makiguchi and Josei Toda, [Image at right] converted to Nichiren Shoshu as lay believers in 1930. They founded Soka Kyoiku Gakkai as a “Value Creation Education Society” and began to recruit lay members. In 1943, Makiguchi and Toda were jailed due to their resistance to the Japanese wartime ideology. Makiguchi died in prison but Toda was freed after the war and revived Soka Gakkai. Soka Gakkai was part of a flowering of new religious movements in postwar Japan, sometimes referred to as “the rush hour of the gods.” By 1960, it was a thriving sect in Japan.

Daisaku Ikeda was inaugurated as third Soka Gakkai president in 1960. As a first step to transform  the Soka Gakkai into a global movement, Ikeda [Image at right] visited the U.S., Canada and Brazil. The First American General Chapter meeting was held in Los Angeles in 1961.

the Soka Gakkai into a global movement, Ikeda [Image at right] visited the U.S., Canada and Brazil. The First American General Chapter meeting was held in Los Angeles in 1961.

The American General Chapter was formed, largely consisting of Japanese war brides who found meaning and community in this new organization. The American movement was built on the foundation of these Japanese war brides (the Pioneer Women of SGI-USA) who helped build a cultural bridge between this obscure Japanese sect and new American members. As late as the 1990’s, these women were still the cultural center of Soka Gakkai, and they worked at almost every Community Center in the U.S. The official leader for most of these years was President George M. Williams (born Masayasu Sadanaga).

In 1963, Soka Gakkai of America was formally incorporated as a non-profit religious organization. George M. Williams devoted himself full time to establishing the practice in America and served as president for a number of years. Three years later, President Ikeda visited the United States and established six new General Chapters. At that time the group also changed its name to Nichiren Shoshu Academy (NSA). A major development for the movement took place in 1967 when it opened its first temples in the U.S., Honseiji Temple in Hawaii and Myoho-ji Temple in Etiwanda, California. High Priest Nittatshu Shonin and President Ikeda were in attendance. The American Joint Headquarters also was formed. The opening of the temples was very significant because only Nichiren Shoshu priests centered in the Temples can ritually bestow Gohonozon replicas to members. The movement began to grow rapidly in 1968 as the counter culture with its message of personal revolution and world peace was peaking. The Myosenji Temple opened in Washington, D.C. in 1972. NSA members donated $100,000,000 toward construction of the Sho-Hondo Grand Main Nichiren Shoshu Temple and attended the completion ceremony at the Head Temple Taiseki-ji at the foot of Mt. Fuji where Nichiren Daishonin’s Dai Gohonzon was enshrined.

During the first half of the 1970s, NSA’s visibility in the U.S. substantially increased. In 1972, Ikeda met for the first time with British historian Arnold J. Toynbee at his home in London; the two collaborated on a dialogue later published as Choose Life. In 1975, he met with U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in Washington D.C. In July 1976, the NSA Bicentennial Convention (Thirteenth General Meeting) was held in New York City with the theme “Toward the Dawn of World Peace.” There was a parade on Fifth Avenue featuring 10,000 group members that attracted 1,000,000 spectators and a “Spirit of ‘76” show. at Shea Stadium. The Bicentennial Convention evidenced a gradual change within the movement from personal practice and development to practice for World Peace and International Cultural Understanding. The movement continued to spread internationally, and was especially popular in Korea and Brazil, while maintaining almost 9,000,000 members in Japan. By 1979, NSA had twenty-two community centers, two training centers, a World Culture Center, and four Nichiren Shoshu Temples in California, Hawaii, Washington, D.C., and New York. In 1979, Daisaku Ikeda was forced to resign as president of Soka Gakkai in Japan following a dispute with the priesthood of Nichiren Shoshu but remained president of Soka Gakkai International (SGI).

During the early 1980s, the movement continued its development apace in the U.S. In 1980, the movement celebrated its twentieth anniversary, which was celebrated in San Francisco with President Daisaku Ikeda in attendance. In that same year, the sixty-seventh Nichiren Shoshu High Priest, Nikken Shonin, enshrined a Joju Gohonzon at the World Culture Center in Santa Monica, with the stated goal of achieving “the accomplishment of the great desire for world peace and kosen-rufu” (converting the majority of the world to Nichiren Shoshu Buddhism). The following year Ikeda made three trips to the United States. The First Grand World Peace Youth Culture Festival also was held in Chicago in 1981, with President Ikeda and High Priest Nikken Shonin. In 1982, 15,000 SGI-USA members travelled to Japan for the Second World Peace Culture Festival. Several Nichiren Shoshu temples were established in the United States so that Soka Gakkai members could experience traditional rituals like receiving a personal Gohonzon (sacred scroll) or weddings and funerals.

The cooperative relationships that had existed through the 1980s, amid simmering tensions, broke down in the early 1990s. In 1991, the Nichiren Shoshu Priesthood excommunicated 11,000,00 Soka Gakkai members worldwide. Most Soka Gakkai members have stayed with the lay organization, although a few moved their Buddhist practice of chanting to the Gohonzon to the Temples run by Nichiren Shoshu priests. This became known to Soka Gakkai members as the “Split” from the priesthood. The Soka Gakkai dissolved their fifty-four year relationship with the Nichiren Shoshu priesthood, and redefined their organization. Soka Gakkai then began developing its distinctive mission in the U.S., which it defined as promotion of world peace, respect for human dignity, and dialogue among people of various viewpoints to achieve those ends. In 1993, the Boston Research  Center for the Twenty-First Century (which changed its name in 2009) to the Ikeda Center for Peace, Dialogue, and Learning was opened in Cambridge, Massachusetts. [Image at right] The center was established to promote conferences and dialogues that work toward a Culture of Peace. It has promoted the idea of Engaged Buddhism, where more than just personal transformation is the purpose of one’s practice. Also in 1993, SGI-USA began conferring Gohonzons to members without participation by the Nichiren Shoshu clergy. In 1995, the SGI-USA formalized its independence when the SGI Charter was approved by the Board of Directors as a clear indication of the purpose of the group.

Center for the Twenty-First Century (which changed its name in 2009) to the Ikeda Center for Peace, Dialogue, and Learning was opened in Cambridge, Massachusetts. [Image at right] The center was established to promote conferences and dialogues that work toward a Culture of Peace. It has promoted the idea of Engaged Buddhism, where more than just personal transformation is the purpose of one’s practice. Also in 1993, SGI-USA began conferring Gohonzons to members without participation by the Nichiren Shoshu clergy. In 1995, the SGI-USA formalized its independence when the SGI Charter was approved by the Board of Directors as a clear indication of the purpose of the group.

In 2000 and thereafter, there were a number of organizational developments. The trade publishing division of SGA-USA, Middleway Press, was founded in 2000. The following year Soka University, a four-year liberal arts college was founded in Aliso Viejo, California to represent Buddhist principles of peace, human rights, and the sanctity of life. The college achieved accreditation and has grown to over 400 students. Daisaku Ikeda began issuing public proposals for addressing world problems: “The Challenge of Global Empowerment: Education for a Sustainable Future” in 2002 and “Fulfilling  the Mission: Empowering the UN to Live Up to the World’s Expectations” in 2006. Minoru Harada was inaugurated as sixth Soka Gakkai president, succeeding Daisaku Ikeda. In 2008 the Washington D.C. Culture of Peace Resource Center [Image at right] was opened on Massachusetts Avenue in the heart of Embassy Row. This center was followed by others in Chicago, New York, San Francisco, Hawaii and Santa Monica, California. SGI-USA announced the Decade of Nuclear Abolition in 2010 as Soka Gakkai members and leaders worked to abolish nuclear weapons around the world and presenting proposals to the United Nations. The first White House Conference of Buddhist Leaders was held in 2015, with significant leadership from SGI-USA, and included representatives of many American Buddhist groups including Soka Gakkai.

the Mission: Empowering the UN to Live Up to the World’s Expectations” in 2006. Minoru Harada was inaugurated as sixth Soka Gakkai president, succeeding Daisaku Ikeda. In 2008 the Washington D.C. Culture of Peace Resource Center [Image at right] was opened on Massachusetts Avenue in the heart of Embassy Row. This center was followed by others in Chicago, New York, San Francisco, Hawaii and Santa Monica, California. SGI-USA announced the Decade of Nuclear Abolition in 2010 as Soka Gakkai members and leaders worked to abolish nuclear weapons around the world and presenting proposals to the United Nations. The first White House Conference of Buddhist Leaders was held in 2015, with significant leadership from SGI-USA, and included representatives of many American Buddhist groups including Soka Gakkai.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

There are three distinctive features of Soka Gakkai: the importance of practice, the absence of moral rules, and the transformative impact of chanting. During the 1970’s, new recruits were told that to practice Nichiren Buddhism there was nothing specific to believe, and, in fact, belief and doctrine were unnecessary. What was important was to practice chanting to the Gohonzon (see below for an explanation) for thirty minutes morning and evening and see the proof of the power of chanting in one’s own life. This leads to a second unique approach that differentiates Soka Gakkai’s practice of Nichiren Buddhism from almost all other religious groups. Soka Gakkai is said to have “no moral rules.” If you simply practice chanting Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo, you will create a life of value. Third, the practice of Nichiren Buddhism as promulgated by Soka Gakkai was first explained in America as “world peace through individual happiness.” Your personal daily chanting practice will transform your life by putting you in rhythm with the law of karma, cause and effect. Whatever cause you make will affect your life, and, ripple through society to create world peace. This basic understanding endures in SGI-USA in the twenty-first century.

Becoming a member means engaging in the three parts of the practice: Faith, Practice, and Study. In addition to the history of the group, there are a number of basic guiding principles that are the focus of study (SGI website):

Human Revolution

“A process of inner transformation and of bringing forth one’s full positive human potential.”

Interconnectedness

“The interconnectedness of life and the idea that nothing exists in isolation, independent of other life.”

Compassion

“Altruistic action that seeks to relieve living beings from suffering and help them attain absolute happiness.”

Wisdom

“That which directs knowledge toward good–toward the creation of value.”

Creating Value

“The positive aspects of reality generated when we creatively engage with the challenges of daily life.”

“An attitude of fundamental respect toward all cultures and every individual, treasuring our differences.”

These contemporary explanations are based on the traditional Nichiren Buddhist Teachings from the writings of Nichiren Daishonin (1222-1282):

Nam-Myoh-Renge-Kyo: Devotion to the Lotus Sutra, also explained as “…devotion to (Nam) the Mystic Law of the Universe (Myoho) creates the vital life-force which includes the simultaneous casue and effect (Renge) of putting human life into rhythm with the universe (Kyo).” (Also called Daimoku).

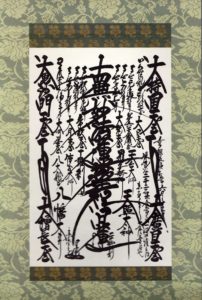

The Gohonzon: Supreme Object of Worship, originally inscribed by Nichiren Daishonin in 1279.

Kosen-rufu: the propagation of Nichiren Daishonin’s teachings throughout the world.

Shakubuku: a powerful method of converting others to the practice of Nichiren Buddhism by breaking their false beliefs and teaching them the practice of True Buddhism.

Ichinen sanzen: Three thousand worlds in a momentary state of existence. The macrocosm of the world can be experienced in the microcosm of your own life.

Karma: Cause and effect as experienced by chanting daimoku to create positive cause for positive effects in your life.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

The rituals and practices of Soka Gakkai involve both the Buddhist practice and the social practices expected of all Soka Gakkai members. New members become Soka Gakkai members for both religious and social reasons. Both aspects of membership create identity, belonging, and a meaning system for Soka Gakkai members.

Members are expected to engage in Faith, Practice and Study. These are defined by Soka Gakkai as chanting daimoku and Gongyo daily, morning and evening (Faith); encouraging other people to become Nichiren Buddhists through shakubuku (Practice); involvement with the community, attending monthly discussion groups and community center events (Practice); and study of the teachings of Nichiren Daishonin and the guidance of Soka Gakkai leaders such as Soka Gakkai International President Daisaku Ikeda by means of Soka Gakkai distributed materials (Study). Many of these are available online to the general public and to “members only” via a membership portal. In the first few decades of Soka Gakkai in America, these materials were printed, and members subscribed to various publications.

Soka Gakkai Buddhist practice is based on “Faith,” chanting nam-myoho-renge-kyo (Daimoku). This is understood by the group to mean “devotion to the Lotus Sutra’ or “…devotion to (Nam) the Mystic Law of the Universe (Myoho) creates the vital life-force which includes the simultaneous cause and effect (Renge) of putting human life into rhythm with the universe (Kyo)” (Hurst 1992:97). In addition, parts of the Lotus Sutra (Gongyo) are also chanted in a Japanese transliteration of the Chinese version of the sutra.

Members chant Daimoku and Gongyo in the morning and the evening for thirty minutes in the presence of a copy of a sacred scroll (Gohonzon) of one of Nichiren Daishonin’s sacred calligraphic  representations of the Lotus Sutra. Amember might chant for longer to achieve specific goals, like chanting for a new car or chanting to restore the relationship with one’s family members or to improve one’s situation at work. Each member is expected to have an altar to house the Gohonzon [Image at right] in one’s home. The altar is only opened to reveal the Gohonzon during chanting sessions.

representations of the Lotus Sutra. Amember might chant for longer to achieve specific goals, like chanting for a new car or chanting to restore the relationship with one’s family members or to improve one’s situation at work. Each member is expected to have an altar to house the Gohonzon [Image at right] in one’s home. The altar is only opened to reveal the Gohonzon during chanting sessions.

The understanding of Soka Gakkai is that chanting creates the life one desires through devotion to the Lotus Sutra. Members are taught to align themselves with the universal law of cause and effect (karma) and create cause to bring the effects they seek. This means that chanting is effective as an everyday practice to improve one’s life in general and as a way to focus on solving specific problems or achieving specific goals.

All Soka Gakkai members are expected to practice shakubuku, recruitment and conversion of new members. This is the most controversial practice in which Soka Gakkai engages. In the 1930s, Japan shakubuku was almost clandestine, since the movement opposed the government, the entry into World War II, and the belief that the emperor was divine. In postwar Japan, with the collapse of a national self-understanding and meaning system, Soka Gakkai seemed to be vindicated by the Empire’s loss of the war and became aggressive in recruiting new members. It was during this time that Soka Gakkai gained a reputation for heavy handedness in its shakubuku efforts. When Soka Gakkai first came to America, brought by Japanese war brides, shakubuku was limited by these pioneer women’s limited English skills and their small social networks.

When Soka Gakkai rode the wave of interest in Asian religions in the 1960s America and began to recruit non-Asian members, shakubuku took on the somewhat aggressive tone that it had had in Japan. Members engaged in street shakubuku, inviting random passersby to “come to a Buddhist meeting.” With time and the maturing of the movement and its members, shakubuku has come to be seen as very soft sell. The current thinking is that through the example of a Soka Gakkai member’s life, others will be attracted to the practice and will ask about it. Then the member shares some information about chanting and invites the potential member to a discussion meeting.

From its earliest days of recruiting, members made the point that Nichiren Buddhism makes no moral judgements. Adherents are free to create the life they want without the limits of the strict moral code espoused by many religious groups. On this basis, Soka Gakkai was one of the first religious groups to openly accept gay members and the enthusiastically encourage members and leaders of all races. As a result, it became the Buddhist group with the largest number of African heritage members in the world. This continues to be true in large cities in America, such as New York, Boston, Chicago, Washington, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia and in Africa itself.

Discussion meetings (Study) are a central part of the Buddhist practice that teaches members the basic beliefs of Nichiren Buddhism and gives them guidance from Soka Gakkai leaders. Discussion meetings also give structure and encouragement to members. They function to bring members together to chant and study, as well as introduce the practice to potential converts. In the 1970’s and 1980’s, discussion groups took place weekly in members’ homes. By the new millennium they were held monthly. Discussion meetings provide community, help in building a practice and provide a place to share experiences that one has had with chanting nam-myoho-renge-kyo.

In addition to Faith, Practice, and Study Soka Gakkai members engage in some life cycle rituals, such as bestowing personal Gonhonzons, weddings and funerals. Before the 1991 schism with the Nichiren Shoshu Priesthood, these were carried out by Nichiren Shoshu priests. Soka Gakkai members would travel to one of the several regional Nichiren Shoshu temples, or a priest would come to the community to perform these functions. After the schism, Soka Gakkai leaders were authorized to carry out these functions.

An additional community practice for Soka Gakkai members has been attending pilgrimages to the Dai Gohonzon in Japan or nationwide Annual General Meetings (Conventions). For example, the 1976 Soka Gakkai Bicentennial Convention was a mix of commitment to Soka Gkkai and patriotic display. Its theme was “Toward the Dawn of World Peace,” and 10,000 members attended. The highlights were a parade down Fifth Avenue with 1,000,000 spectators, and a “Sprit of ‘76” show performed at the break between the two games of a double header at Shea stadium.

General Meetings continued to be held on a regular basis throughout North America. Meetings have been held in San Francisco, Hawaii, Chicago, and New York. Some years these are held as Culture Festivals on various themes, such as the 1986 “Year of Raising Capable People,” with participation in the Cherry Blossom Parade in Washington, D.C. Members are strongly encouraged to attend these meetings and festivals.

Pilgrimage was part of the early Soka Gakkai tradition. However, after the 1991 schism, Soka Gakkai pilgrimages to Japan ceased and group activities focused on the U.S.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

The SGI-USA organization is hierarchical and is based on a Japanese model, with a Men’s Division, a Women’s Division, a Young Men’s Division and a Young Women’s Division. These are understood as natural affinity groups. Because they are somewhat separate but operate within a context of overall male leadership, there are opportunities for women and youth to take responsibility and develop leadership skills. Leaders are appointed by those at the level above. So, the American SGI President is appointed by Soka Gakkai in Japan, and the U.S. hierarchy grades downward from Region to Area to Chapter to the most local neighborhood District.

This straightforward approach has been successful for SGI-USA, and leaders generally are respected.  However, it is usually the higher level leaders who are treated with reverence and assumed to have superior qualities and judgement. Certainly Nichiren Daishonin [Image at right] is revered, as are the deceased past presidents of Soka Gakkai and President Ikeda, who led Soka Gakkai as it became an international movement. For several decades, President Ikeda’s picture was in every district meeting place, usually a member’s home. His guidance, as it appeared in SGI publications, was and still is highly respected.

However, it is usually the higher level leaders who are treated with reverence and assumed to have superior qualities and judgement. Certainly Nichiren Daishonin [Image at right] is revered, as are the deceased past presidents of Soka Gakkai and President Ikeda, who led Soka Gakkai as it became an international movement. For several decades, President Ikeda’s picture was in every district meeting place, usually a member’s home. His guidance, as it appeared in SGI publications, was and still is highly respected.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

The schism that developed out of conflicts between the leadership of the Soka Gakkai and the Head Priest of the Nichiren Shoshu came to a head in 1991 when the High Priest Nikken Shonin excommunicated 11,000,000 Soka Gakkai members. This event is still contentious for the Nichiren Shoshu, which insists that the Soka Gakkai has deviated from the correct practice of Nichiren Buddhism. New lay organizations have been created by the Nichiren Shoshu to fill the void left by the Soka Gakkai. It seems less important to Soka Gakkai which has assumed independent spiritual authority by making its own copies of the Gohonzon to give to new members and has adjusted to life without a priesthood. The long-term relationship between SGI-USA and the Nichiren Shoshu thus remains to be determined.

The Soka Gakkai will face a major moment of transition when Daisaku Ikeda, who reached his ninetieth birthday in 2018, is no longer able to lead the movement. President Ikeda was born in 1928 and became Soka Gakkai President in 1960. He led the Soka Gakkai as they became a political power through the Komeito political party in Japan. He led the movement as it spread around the world and became SGI. He guided the organization in the schism with the Nichiren Shoshu Priesthood in 1991 and helped it envision itself as an independent lay organization of Nichiren Buddhists. Indeed, members today use the phrase “Soka Gakkai Buddhism;” prior to the schism Soka Gakkai referred to itself as “Nichiren Shoshu Buddhism.” Ikeda has helped stabilize the group as it enters the twenty-first century and has come to understand itself as “Buddishm in Action for Peace: Empowering Individuals toward Positive Global Change.” Ikeda is spoken of reverently; his picture hangs in community centers. The challenge of holding together a complex international movement is now on the horizon.

IMAGES

Image #1: Josei Toda.

Image #2: Daisaku Ikeda.

Image #3: Ikeda Center for Peace, Dialogue, and Learning.

Image #4: Washngton D.C. Culture of Peace Resource Center.

Image #5: The Gohonzon.

Image #6: Nichiren Daishonin.

REFERENCES**

** Unless otherwise note, this profile is drawn from Jane Hurst. 1992. Nichiren Shoshu Buddhism and the Soka Gakkai in America: The Ethos of a New Religious Movement. New York: Garland.

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Anesaki, Masaharu. Nichiren, The Buddhist Prophet. 1966. Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith.

Bethel, Dayle M. 1973. Makiguchi, the Value Creator. New York: John Weatherhill.

Causten, Richard. 1991. “Freedom and Democracy: To Be or Not To Be.” Issues Between the Nichiren Shoshu Priesthood and the Soka Gakkai, Volume 1. Tokyo: Soka Gakkai International.

Causten, Richard. 1989. Nichiren Shoshu Buddhism. New York: Harper and Row.

Causten, Richard. 1962. The Sokagakkai. Second Edition. Tokyo: Seikyo Press.

Chappell, David, ed. 1999. Buddhist Peacework: Creating Cultures of Peace. Boston, Wisdom Publications.

Dator, James Allen. 1969. Sokagakkai, Builders of the Third Civilization. (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press.

Dobbelaere, Karel. 2001. Soka Gakkai: From Lay Movement to Religion. Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books.

Ellwood, Robert S. 1974. The Eagle and the Rising Sun: Americans and the New Religions of Japan. Philadelphia, PA: Westminster Press.

Hammond, Phillip and Machacek, David. 1999. Soka Gakkai in America: Accommodation and Conversion. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hashimoto, Hideo and William McPherson. “Rise and Decline of Sokagakkai, Japan and the United States.” Review of Religious Research17.2 (1976): 82-92.

“History and Development of Soka Gakkai and Soka Gakkai International.” 1992. Photocopy: Soka Gakkai International.

Hurst, Jane. 2001. “A Buddhist Reformation in the Twentieth Century: Causes an Implication of the Conflict between th Soka Gakkai and the Nichiren Shoshu Priesthood.“ Pp. 67-96 in Global Citizens: The Soka Gakkai Buddhist Movement in the World, edited by David Machacek and Bryan R. Wilson. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hurst, Jane. 2000. “A Buddhist Reformation in the Twentieth Century: Causes and Implications of the Conflict between the Soka Gakkai and the Nichiren Shoshu Priesthood,” Pp. 67-96 in Global Citizens: The Soka Gakkai Buddhist Movement in the World, edited by David Machacek and Bryan Wilson. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hurst, Jane. 1998. “Nichiren Shoshu and Soka Gakkai in America: The Pioneer Spirit.” Pp. 79-98 in The Faces of Buddhism in America, edited by Charles S. Prebish and Kenneth K. Tanaka. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hurst, Jane. 1995. “Buddhism in America: The Dharma in the Land of the Red Man.” Pp. 161-73 in America’s Alternative Religions, edited by Timothy Miller. Albany, State University of New York Press.

Hurst, Jane. 1992. Nichiren Shoshu Buddhism and the Soka Gakkai in America: The Ethos of a New Religious Movement. New York: Garland Press.

Ikeda, Daisaku. 1995. The New Human Revolution. Santa Monica, CA: World Tribune Press.

Ikeda, Daisaku. 1972-1984. The Human Revolution. 5 Volumes. Condensed version of the Japanese original. New York and Tokyo: Weatherhill.

Ikeda, Daisaku and Watson, Burton. 2008. The Living Buddha: An Interpretive Biography (Soka Gakkai History of Buddhism) Santa Monica, CA: Middleway Press.

“Issues between the Nichiren Shoshu Priesthood and the Soka Gakkai,” Volumes 1-3. 1991. Tokyo: Soka Gakkai International.

Jordan, Mary. 1998. “A Major Eruption At the Foot of Fuji: Feud Brings Acclaimed Temple to Brink of Demolition” Washington Post Foreign Service, June 14, G01.

Lauer, Helen. 1975. “A Study of the Nichiren Shoshu Academy of America.” CCNY Journal of Anthropology I:7-26.

Layman, Emma McCoy. 1977. Buddhism in America. Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

McPherson, William. 1977. “Nichiren Shoshu of America, 1972-1977.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, Chicago, IL, October, 1977.

Metraux, Daniel. 1996. The Lotus and the Maple Leaf. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1996.

Metraux, Daniel. 1994. The Soka Gakkai Revolution. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Melton, J. Gordon. 1986. “Nichiren Shoshu Academy, Soka Gakkai.” Pp. 171-75 in Encyclopedic Handbook of Cults in America. New York and London: Garland.

Morris, Ivan. 1965 .“Soka Gakkai Brings ‘Absolute Happiness’.” New York Times Magazine, July 18, 8-9, 36, 38-39.

Murata, Kiyoaki. 1969. Japan’s New Buddhism: An Objective Account of Sōka Gakkai. New York: Walker / Weatherhill.

Nichiren Daishonin. 1979-1990. The Major Writings of Nichiren Daishonin. Volumes I-VI. Tokyo: Nichiren Shoshu International Center.

NSA Bicentennial Convention Graphic. 1976. Santa Monica, CA: World Tribune Press.

NSA Quarterly. 1973-1977. Santa Monica, CA : World Tribune Press.

Ourvan, Jeffrey. 2016. The Star Spangled Buddhist: Zen, Tibetan, and Soka Gakkai Buddhism and the Quest for Enlightenment in America. New York, NY: Skyhorse Publishing,

Parks, Yoko Yamamoto. 1984. “Chanting is Efficacious: Changes in the organization and Beliefs of the American Sokagakkai (Japan).” Ph.D. dissertation. University of Pennsylvania.

Prebish, Charles W. 2003. Buddhism, the American Experience. JBE Online Books.

Prebish, Charles W. 1979. American Buddhism. North Scituate, MA: Duxbury Press.

Queen, Christopher S., ed. 2000. Engaged Buddhism in the West. Boston: Wisdom Publications.

Seager, Richard Hughes. 2006. Encountering the Dharma: Daisaku Ikeda, Soka Gakkai, and the Globalization of Buddhist Humanism. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Strand, Clark. 2014. Waking the Buddha: How the Most Dynamic and Empowering Buddhist Movement in History Is Changing Our Concept of Religion. Santa Monica, CA: Middleway Press.

Snow, David A. 1987. “Organization, Ideology and Mobilization: The Case of Nichiren Shoshu of America.” Pp. 153-72 in The Future of New Religious Movements, edited by David G. Bromley and Phillip E. Hammond. Macon, GA.: Mercer University Press.

“The Excommunication of the Soka Gakkai?” 1991. World Tribune, November11.

Williams, George M. 1974. NSA Seminars. Santa Monica, CA: World Tribune Press.

Wilson, Bryan and Karen Dobbelaere. 1998. A Time to Chant: The Soka Gakkai Buddhists in Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

World Tribune Graphic, Special Commemorative Sho Hondo Edition. 1972. Santa Monica, CA: World Tribune Press.

Post Date:

4 July 2018