JEDI COMMUNITY TIMELINE

1977: Star Wars, later renamed Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope, premiered. It introduced the notions of the Force and the Jedi Knights and won six Oscars.

1988: Mythologist Joseph Campbell told Bill Moyers that he considered Star Wars to be a modern myth.

1998: The Jedi Academy, a website including the first online discussion forum for Jedi Realists, was founded by Baal Legato.

2001: The Jedi Census Phenomenon. More than 500,000 individuals filled in “Jedi” as their religious affiliation in New Zealand, Canada, Great Britain, and Australia combined.

2001: Jediism: The Jedi Religion was founded by David Dolan. It remained the main online Jediist group until 2005.

2002: The first national gathering of the Jedi Community in the United States took place.

2005: Rev. John Henry Phelan (aka Brother John) founded the Temple of the Jedi Order, which became the most-trafficked Jediist website.

2007: Daniel Jones founded the Church of Jediism in the United Kingdom.

2015: The Jedi Compass: Collected Works of The Jedi Community was published.

2016: Temple of the Jedi Order applied for legal recognition in the United Kingdom as a religious institution but was turned down.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

The Jedi Community is a fiction-based religious milieu (cf. Davidsen 2013) centred on George Lucas’ Star Wars movies. From Star Wars the real-life Jedi have adopted the identity as Jedi Knights and a belief in the Force,  the non-personal, cosmic power in the Star Wars universe. The first Star Wars movie premiered in 1977, [Image at right] and in an interview Lucas said that he “put the Force into the movie in order to awaken a certain kind of spirituality in young people” (Moyers 1999; cf. also Davidsen 2016a:381-82). It was not until 1995, however, that the Jedi Community started to emerge from the online Star Wars roleplaying community. At this time a group of Star Wars roleplayers, who would eventually adopt the designation Jedi Realists for themselves, began to discuss how to apply the ideals of the Jedi Knights in their own lives. Their ambition was to recreate, as accurately as possible, the Jedi Knights of Star Wars in the real world, and central to this endeavor was the establishment of online education centers in which members could study the Jedi ethics and learn about the Force.

the non-personal, cosmic power in the Star Wars universe. The first Star Wars movie premiered in 1977, [Image at right] and in an interview Lucas said that he “put the Force into the movie in order to awaken a certain kind of spirituality in young people” (Moyers 1999; cf. also Davidsen 2016a:381-82). It was not until 1995, however, that the Jedi Community started to emerge from the online Star Wars roleplaying community. At this time a group of Star Wars roleplayers, who would eventually adopt the designation Jedi Realists for themselves, began to discuss how to apply the ideals of the Jedi Knights in their own lives. Their ambition was to recreate, as accurately as possible, the Jedi Knights of Star Wars in the real world, and central to this endeavor was the establishment of online education centers in which members could study the Jedi ethics and learn about the Force.

The earliest Jedi Realist website was probably Kharis Nightflyer’s Jedi Praxeum on Yavin 4 (launched in December 1995), but Baal Legato’s Jedi Academy (active 1998-2003), which included an active discussion forum, was the first real meeting place for Jedi Realists and the central hub in the Jedi Community between 1999 and 2002 (Macleod 2008:16). In their attempt to recreate the Jedi way of life, Jedi Realists not only based themselves on the Star Wars movies. They also drew inspiration from Jedi-focused supplements to Star Wars: The Roleplaying Game and from Kevin J. Anderson’s Jedi Academy trilogy (1994) which tells of Luke Skywalker’s restoration of the Jedi Order and his training of a new generation of Jedi Knights (cf. Davidsen 2017:12-13). Reflecting their RPG-heritage, most of the big Jedi Realist sites in the early years, including Jedi of the New Millennium (active 1997-2004), Jedi Creed (active 1999-2001), and Jedi Temple (active 2000-2009), combined roleplaying and serious Jedi training on their sites (Macleod 2008:14, 21), but around 2000 Jedi Realist groups started to emerge that had cut their ties to the community’s roleplaying past. These groups included Temple of the Jedi Arts (active 2000-2005) and the influential Jedi Organization (later renamed JEDI; active 2001-2006).

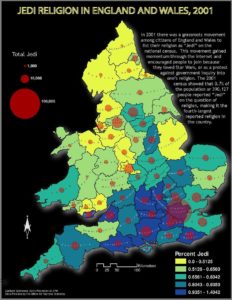

In 2001, more than 500,000 people in New Zealand, Australia, Canada, and Great Britain combined gave up  their religious affiliation as “Jedi” in the national censuses in response to a media-hyped chain mail that had circulated in advance of the surveys (Porter 2006:96-98; Possamai 2005:72-73; Singler 2014:154; Davidsen 2017:15). Whereas this so-called Jedi Census Phenomenon was initiated by individuals who were not involved in the Jedi Community proper, it impacted the Jedi Community in several ways. Some of the older Jedi Realists groups, including Jedi Creed, dissolved due to internal disputes about how to handle the sudden media attention (Davidsen 2017:14). Most importantly, however, the Jedi Census Phenomenon inspired individuals to found a new type of Jedi groups that referred to themselves as churches (rather than as academies) and whose members considered themselves to be followers of a genuine religion, Jediism. David Dolan’s group Jediism: The Jedi Religion was the first such group. It became inactive in 2006, but among its direct successors were many influential Jediist groups, including Jedi Sanctuary (active 2003-2007) and Temple of the Jedi Order (founded 2005 by John Henry Phelan). The most prominent Jediist groups unrelated to Jediism: The Jedi Religion are the New Zealand-based Jedi Church (founded 2003) and the U.K.-based Church of Jediism (founded 2007 by Daniel Jones).

their religious affiliation as “Jedi” in the national censuses in response to a media-hyped chain mail that had circulated in advance of the surveys (Porter 2006:96-98; Possamai 2005:72-73; Singler 2014:154; Davidsen 2017:15). Whereas this so-called Jedi Census Phenomenon was initiated by individuals who were not involved in the Jedi Community proper, it impacted the Jedi Community in several ways. Some of the older Jedi Realists groups, including Jedi Creed, dissolved due to internal disputes about how to handle the sudden media attention (Davidsen 2017:14). Most importantly, however, the Jedi Census Phenomenon inspired individuals to found a new type of Jedi groups that referred to themselves as churches (rather than as academies) and whose members considered themselves to be followers of a genuine religion, Jediism. David Dolan’s group Jediism: The Jedi Religion was the first such group. It became inactive in 2006, but among its direct successors were many influential Jediist groups, including Jedi Sanctuary (active 2003-2007) and Temple of the Jedi Order (founded 2005 by John Henry Phelan). The most prominent Jediist groups unrelated to Jediism: The Jedi Religion are the New Zealand-based Jedi Church (founded 2003) and the U.K.-based Church of Jediism (founded 2007 by Daniel Jones).

In the twenty-first century, the most important development in the Jedi Community has been the emergence of groups that meet in real life rather than on the Internet. These groups include the Chicago Jedi (founded 2006) and the California Jedi (founded 2012), as well as similar groups outside the United States. In America, where most Jedi live, a yearly national gathering has been organized since 2002. Local and national gatherings, attracting both Jedi Realists and Jediists, are advertised throughout the Jedi Community and are supported by Facebook groups and a dedicated national gathering website (Davidsen 2017:17-18).

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Jedi of all stripes agree that Star Wars is their core source of inspiration, but they also hold, as a matter of course, that Star Wars is fiction. That is to say: the Jedi do not consider the storyline or the characters of Star Wars to be real, and they do not regard George Lucas as a prophet, but they do consider the Force to be a valid term for a real, cosmic power existing in the real world. They also consider the Jedi Knights of Star Wars to be role models whose values and ideals are universal and worth aspiring to.

Two additional shared characteristics follow logically from the acceptance of Star Wars as the Jedi Community’s scriptural center. First, all Jedi groups adhere to some version of the Jedi Code, the first version of which was published in 1987 in Star Wars: The Roleplaying Game (Costikyan 1987:69). This version, often referred to as the “Orthodox Code,” runs as follows:

There is no emotion, there is peace.

There is no ignorance, there is knowledge.

There is no passion, there is serenity.

There is no death, there is the Force.

The second Star Wars-determined common denominator of all Jedi groups is a doctrinal emphasis on cosmology (and ethics), rather than on cosmic history and salvation. This emphasis is not random, but follows quite naturally from the type of religious beliefs ‘afforded’ by the Star Wars narrative (cf. Davidsen 2016b). Indeed, in the teachings of the Jedi Knights in Star Wars we find articulate ideas about the existence and nature of the Force (religious cosmology), and the related belief that each individual possesses a spirit or soul that is somehow connected to the Force and returns to ‘the Netherworld of the Force’ after death (religious anthropology). By contrast, Star Wars Jedi are silent on matters of cosmic history. They have nothing to say on how and why the world came into being (protology), nor on matters of eschatology or soteriology. The Jedi in the real world stick to the same emphasis: they believe in the Force and argue that upon death the individual soul/spirit returns to or merges with the cosmic Force. They have not developed significant protological or soteriological doctrines, even though some Jediists will say that the Force has a plan for us and that everything happens for a purpose.

Within the Jedi Community there are also substantial disagreements, and these concern beliefs, rituals, and organizational style. Differences on these parameters largely correlate with each other and with the self-identification as Jedi Realist vis-à-vis Jediist. In terms of doctrine, the main difference between Jedi Realists and Jediists concerns their view of the Force, their “dynamology.” Jedi Realists tend to view the Force in dynamistic terms, as a relatively passive and vitalistic power or life energy. The Force Academy and the Ashla Knights, for example, compare the Force with Eastern concepts, such as chi and prana, and observe similarities between their own practice and tai chi, aikido, and Zen. Jediist groups, by contrast, combine dynamism with a more animistic conception of the Force as an independent agent who can intervene in the world and who it therefore makes sense to address in prayer.

Another point of doctrinal dispute concerns which other sources than the Star Wars movies one can legitimately draw on when putting together doctrines and rituals for one’s Jedi path. One camp (I shall call them purists) argue that the movies should be supplemented only by material from what Star Wars fans refer to as the Expanded Universe, i.e. the officially licensed Star Wars novels, video games, and roleplaying games. This purist stance was the norm when Jedi Realism first emerged out of the Star Wars roleplaying community. Over the decades, however, an increasing number of individuals have been attracted to Jedi Realism and Jediism who like the Star Wars movies but are not hardcore Star Wars fans. Partly for this reason, most Jedi today, including all Jediists and many Jedi Realists, can better be described as syncretics, in the sense that they draw on both Star Wars and material from conventional religions when constructing their doctrines and training practices. In fact, these Jedi themselves often use the term “syncretism” to refer their practice of bricolage. Both Jedi Realist and Jediist syncretics study New Age and Western Buddhist literature, such as Alan Watt’s The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are (1966) and Dan Millman’s Way of the Peaceful Warrior (1984). In addition, Jediist syncretics often draw inspiration from Christianity. For example, Temple of the Jedi Order has formulated a Jedi Creed that is in fact a modified version of one of Francis of Assisi’s prayers (The Way of Jediism 2010:10). Several movement intellectuals within the Jedi Community have published books about the Jedi path (see Davidsen 2017:25 for references), and leaders from across the Jedi Community have worked together to publish two collections of essays, The Great Jedi Holocron (Yaw 2006) and Jedi Compass (Jedi Community 2015).

RITUALS/PRACTICES

The religion of the Jedi Knights in Star Wars is devoid of most of those practices that people normally associate with a “real” religion. The Star Wars movies feature no prayers, creeds, sacrifices, sermons, or rites of passage, but the Jedi (and other characters) use the benediction “May the Force Be With You” as a farewell greeting and we see various Jedi Knights meditate (and Darth Vader too; he has a meditation egg). Naturally, the Jedi Community has adopted both the Force benediction (sometimes abbreviated MTFBWY) and meditation.

While meditation is clearly important, most Jedi actually spend more time on two other practices: self-betterment and community service. The Jedi ethic of self-betterment prescribes both physical and intellectual training, and most Jedi practice martial arts, study the Force, and contribute to community discussions on the Jedi way of life. In addition, all Jediists (but only some Jedi Realists) consider community service to be a hallmark of Jedihood. Some Jediist groups have even developed more or less institutionalized community service programs. The Order of the Jedi (Canada), for example, used to place offers for help on community bulletin boards, or worked incognito, leaving just an anonymous assist card with the wording:

A helping hand was provided by,

a member of the:

Order of the Jedi Canada

Commited [sic] to teaching solid values,

through strong moral and ethical guidance (quoted in Vossler 2009:66).

Whereas Jedi Realists and Jediists share the emphasis on meditation, self-betterment, and (to some extent) community service, only Jediists aim to develop all the ritual practices that a full-fledged religion needs but that Star Wars lacks. And of all Jediist groups, the Temple of the Jedi Order has developed the most complete liturgy. Besides rituals for initiation as Knight (for which all other Jedi groups have equivalents), the Temple of the Jedi Order has created rituals for marriages and funerals and for the consecration of land and temples (The Way of Jediism 2010). Furthermore, as members of the group explain, the Temple produces “regularly published written sermons every five days, with forth-nightly, real time live services in the TotJO website’s chat room” (Williams, Miller, and Kitchen 2017:121). These services usually end with a group recitation of the Jedi Creed (Williams, Miller, and Kitchen 2017:131). Throughout the group’s history, members have worked within five “special interest groups” (formerly “rites”) that developed additional rituals for members of various religious observances. The five special interest groups are Pure Land (here meaning Star Wars only), Abrahamic, Pagan, Buddhist, and Humanist (The Way of Jediism 2010:18).

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

All Jedi groups are organized as initiatory orders and require a certain amount of study, the approval of a master, and sometimes success on a formal exam before one can advance to the rank of full, initiated member. Those who have achieved this rank are usually referred to as Jedi Knights. Study programs typically involve two phases. First, students are required to work through a set curriculum on the religion of the Jedi Knights in Star Wars, the history of the real-world Jedi Community, and additional material, such as books by Alan Watts and Joseph Campbell. During  this phase, students also familiarize themselves with key doctrinal texts produced by members of the Jedi Community, such as Jedi Kidohdin’s “16 Basic Teachings” and Jedi Opie Macleod’s “Jedi Circle” (Trout 2012). [Image at right] The second phase involves individualized study under the guidance of a Jedi Master. Like in Star Wars, Jedi Knights (and Jedi holding equivalent titles) are entitled to train novices up to the rank of Knight. The advancement to the rank of Knight comes with a ritual in which the knight-to-be takes a vow and is formally knighted. Jedi Knights who have raised a certain number of other Jedi to the rank of Knight (three in the Temple of the Jedi Order; two in the Jedi Academy Online) and who have proved themselves worthy in other ways as well, gain the rank of Jedi Master.

this phase, students also familiarize themselves with key doctrinal texts produced by members of the Jedi Community, such as Jedi Kidohdin’s “16 Basic Teachings” and Jedi Opie Macleod’s “Jedi Circle” (Trout 2012). [Image at right] The second phase involves individualized study under the guidance of a Jedi Master. Like in Star Wars, Jedi Knights (and Jedi holding equivalent titles) are entitled to train novices up to the rank of Knight. The advancement to the rank of Knight comes with a ritual in which the knight-to-be takes a vow and is formally knighted. Jedi Knights who have raised a certain number of other Jedi to the rank of Knight (three in the Temple of the Jedi Order; two in the Jedi Academy Online) and who have proved themselves worthy in other ways as well, gain the rank of Jedi Master.

The Jedi Community is a diverse milieu composed of several independent orders and chapters. As such, the Jedi Community does not have a single leader who can speak for the entire community, though it fields several influential movement intellectuals, including Jedi Opie Macleod (Jedi Academy Online) and Brother John Phelan (Temple of the Jedi Order). Crucially, and in contrast to many other new religious movements, none of the intellectual leaders of the Jedi Community has put forward a claim to extraordinary charismatic status. Leaders do not claim to receive exclusive revelations from the Force, nor do they claim that the Force gives them healing or mind-reading powers beyond what an average Jedi can aspire to. In a much more down-to-earth fashion leaders within the Jedi Community gain authority and prestige by contributing constructively to the collective project of defining what being a Jedi is all about, and by facilitating this ongoing discussion as reliable administrators. Perhaps charisma has been routinized within the Jedi Community right from the start because the role of charismatic founder figures has already been filled by the Jedi characters from the Star Wars movies. Despite the multi-cephalous nature of the Jedi Community, coherence is promoted by cooperative initiatives, such as the national gathering in the U.S. (since 2002) and the digital quarterly The Holocron (launched 2015), as well as by the fact that most Jedi are members of several groups at the same time.

The 2001 census counted half a million Jedi, but it is difficult to estimate how many members are actually active within the Jedi Community. Leading members of the Temple of the Jedi Order estimate the total number of registered members in the group to be around 2,000, of which no more than 200 make up the active core; world-wide they estimate the total number of Jedi to be no higher than 4,000-5,000 (Williams, Miller, and Kitchen 2017:132-33). This is obviously a rough estimate, but it seems clear that whereas the census measured Jedi in the hundreds of thousands, it is more realistic to measure active members of the Jedi Community in the thousands and sympathizers and passive members by the tens of thousands. Geographically, most Jedi hail from the United States, the United Kingdom, and other English-speaking countries, but there are also local Jedi chapters and non-Anglophone Facebook groups based in for example Denmark and Brazil. Most Jedi are white males, aged twenty to forty4 (Williams, Miller, and Kitchen 2017:132), but the increase in offline activities seems to have made the Jedi Community more attractive also to females.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

All members of the Jedi Community agree that the way of the Jedi is genuine and serious, but there is outspoken disagreement on the question whether Jedi groups, as a consequence of this, should also strife for legal recognition as a religion. Legal recognition is a main objective for Jediists, but Jedi Realists reject this project because they consider the Jedi Path to be a (liberating) philosophy of life rather than a (dull) religion.

The first Jediist group to receive legal recognition as a religion was the Temple of the Jedi Order, which was incorporated as a non-profit corporation with 501(c)(3) U.S. tax status in its home state of Texas by John Henry Phelan (aka Brother John) on December 25, 2005 (Singler 2014:164). In seeking legal recognition, Phelan was inspired by an earlier Jediist group, Jedi Sanctuary, which had been registered as a congregation within the Universal Life Church (ID number 61842) and as such had attained the right to ordain ministers and to issue BA, MA, and Doctorate Degrees in Divinity. By registering the Temple of the Jedi Order as a church in its own right, Phelan not only attained tax exemption for his group, but also received the right to ordain ministers who can work as certified marriage celebrants. The Temple also gained the right to offer its own Degrees in Divinity (Jediism). The group now hands out the Associate Degree of Divinity to initiated Knights and the Bachelor Degree in Divinity to Senior Knights; the Doctorate of Divinity is reserved as an honorary degree (Williams, Miller, and Kitchen 2017: 130-31). Following the example of the Temple of the Jedi Order, the Order of the Jedi (Canada) applied for status as a non-profit religious body and was granted this status in its home-country in 2009 (McCormick 2012:178) and in the United States in 2012.

In contrast to the Temple of the Jedi Order and the Order of the Jedi (Canada), Daniel Jones’ UK-based Church of Jediism is incorporated as a for-profit organization (limited company) (Singler 2014:164). Within the Jediist camp, the Church of Jediism also sticks out in other ways. For example, Church of Jediism’s campaign for legal recognition as a religion is carried out in a seemingly tongue-in-cheek style that resembles the ludic happenings of the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster. Not unlike the Pastafarians who want to wear a colander on their driver’s license photographs, Daniel Jones accused supermarket chain Tesco for religious discrimination after he was asked to de-hood in one of their stores (Carter 2009). It is also characteristic of Church of Jediism’s style that the organization’s new website was launched on “May the Fourth” 2017, a major day of celebration for Star Wars fans, but hardly the most authentic-looking holiday for a serious religious group.

The for-profit incorporation and the parodic attitude of the Church of Jediism, as well Daniel Jones’ propensity to make hyperbolic claims about the size and age of his organization, have caused frustration for the Temple of the Jedi Order and likeminded groups who feel encumbered in their battle for admission into the club of legit religions (cf. Singler 2015:170-71). Indeed, from the perspective of these groups, the fight for recognition as a genuine religion must be fought on two fronts, both without the Jedi Community and within it. It was a significant disappointment that the Temple of the Jedi Order’s application for official recognition as a religious charity organization in the United Kingdom was turned down in late 2016 on the grounds that the group’s beliefs were not serious enough. A report from the United Kingdom’s official charity regulator stated that

the Commission is not satisfied that the “Live Services” on the website, the published sermons and the promotion of meditation evidence a relationship between the adherents of the religion and the gods, principles or things which is expressed by worship, reverence and adoration, veneration intercession or by some other religious rite or service (quoted in Bingham 2016).

The negative ruling may have been influenced by the fact that the Church of the Jediism, and not the Temple of the Jedi Order, is the public face of Jediism in the United Kingdom.

IMAGES

Image #1: Star Wars: The Jedi Academy Triology.

Image #2: Map of distribution of individuals identifying as members of the Jedi community in England and Wales, 2001.

Image #3: Photograph of Trout’s The Jedi Circle: Jedi Philosophy for Everyday Live.

REFERENCES

Anderson, Kevin J. 1994. Jedi Academy. Toronto: Bantam Books. (Includes the titles Jedi Search, Dark Apprentice, and Champions of the Force.)

Bingham, John. 2016. “Bad News for Star Wars Obsessives: Jediism Officially Not a Religion.” The Daily Telegraph, December 19. Accessed from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/12/19/bad-news-star-wars-obsessives-jediism-officially-not-religion on 5 April 2017.

Carter, Helen. 2009. “Jedi Religion Founder Accuses Tesco of Discrimination Over Rules on Hoods.” The Guardian, September 18. Accessed from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/sep/18/jedi-religion-tesco-hood-jones on 5 April 2017.

Costikyan, Greg. 1987. Star Wars: The Roleplaying Game. New York: West End Games. Second Edition 1992; Second Edition, Revised and Expanded 1996.

Davidsen, Markus Altena, 2017. “The Jedi Community: History and Folklore of a Fiction-based Religion.” New Directions in Folklore 15:7-49 (Special Issue: “The Folk Awakens: Star Wars and Folkloristics,” edited by John E. Price).

Davidsen, Markus Altena. 2016a. “From Star Wars to Jediism: The Emergence of Fiction-based Religion.” Pp. 376-89, 571-75 in Words: Religious Language Matters, edited by Ernst van den Hemel and Asja Szafraniec. New York: Fordham University Press.

Davidsen, Markus Altena. 2016b. “The Religious Affordance of Fiction: A Semiotic Approach.” Religion 46:521-49. (Published open access and available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0048721X.2016.1210392).

Davidsen, Markus Altena. 2013. “Fiction-based Religion: Conceptualising a New Category against History-based Religion and Fandom.” Culture and Religion: An Interdisciplinary Journal 14:378-95.

Jedi Community. 2015. The Jedi Compass: Collected Works of The Jedi Community. CreateSpace.

Macleod, Opie. 2008. “History of the Jedi Community 1998-2008.” Accessed from http://www.templeofthejediorder.org/media/kunena/attachments/523/h979ab0a.pdf on 4 March 2017.

McCormick, Debra. 2012. “The Sanctification of Star Wars: From Fans to Followers” Pp 165-84 in Handbook of Hyper-real Religions, edited by Adam Possamai. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

Moyers, Bill. 1999. “Of Myth and Men: A Conversation between Bill Moyers and George Lucas about the Meaning of the Force and the True Theology of Star Wars.” Time, April 26. Accessed from http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,23298-1,00.html on 30 March 2017.

Porter, Jennifer F. 2006. ““I am a Jedi”: Star Wars Fandom, Religious Belief, and the 2001 Census.” Pp. 95-112 in Finding the Force of the Star Wars Franchise: Fans, Merchandise, & Critics, edited by Matthew Wilhelm Kapell and John Shelton Lawrence. New York: Peter Lang.

Possamai, Adam. 2005. Religion and Popular Culture: A Hyper-Real Testament. Brussel: P. I. E. Peter Lang.

Singler, Beth. 2015. “Internet-Based New Religious Movements and Dispute Resolution.” Pp. 161-78 in Religion and Legal Pluralism, edited by Russell Sandberg. Farnham: Ashgate.

Singler, Beth. 2014. “’See Mom It Is Real’: The UK Census, Jediism and Social Media.” Journal of Religion in Europe 7:150-68.

The Way of Jediism. 2010. Published by the Temple of the Jedi Order. Accessed from https://www.templeofthejediorder.org/media/kunena/attachments/523/haab2b3a_2014-11-19.pdf on 4 April 2017.

Trout, Kevin S. (Opie Macleod). 2012. The Jedi Circle: Jedi Philosophy for Everyday Life. Valencia, CA: The Jedi Academy Online.

Vossler, Matthew T. 2009. Jedi Manual Basic: Introduction to Jedi Knighthood. Rockville, MD: Dreamz-Work Publications.

Williams, Ash, Benjamin-Alexandre Miller, and Michael Kitchen. 2017. “Jediism and the Temple of the Jedi Order.” Pp. 119-33 in Fiction, Invention and Hyper-reality: From Popular Culture to Religion, edited by Carole M. Cusack and Pavol Kosnáč. London and New York: Routledge.

Yaw, Adam, ed. 2006. The Great Jedi Holocron. Accessed from http://ashlaknights.net/support_documents/The%20Great%20Jedi%20Holocron%20-%20By%20Adam%20Yaw%202006.pdf. on 4 April 2017.

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Ashla Knights website. Accessed from http://www.ashlaknights.net on 4 April 2017.

Church of Jediism website. Accessed from https://thechurchofjediism.org on 28 June 2017.

Force Academy website. Accessed from http://www.forceacademy.co.uk on 14 March 2017.

Institute of Jedi Realist Studies website. Accessed from http://instituteforjedirealiststudies.org on 4 April 2017.

Jedi Church website. Accessed from http://www.jedichurch.com on 4 April 2017.

Temple of the Jedi Order website. Accessed from http://www.templeofthejediorder.org 4 April 2017.

Post Date:

21 February 2018