ADIDAM TIMELINE

1939 (3 November) Franklin Albert Jones was born in Long Island, New York.

1964-1970 Jones searched for ultimate truth, using psychoactive drugs. He followed several gurus and self-designed introspective processes.

1968-1969 Jones spent a year as a full-time employee/practitioner of Scientology.

1970 Jones reported attaining “complete enlightenment.” This was just one of several dramatic transformations he claims to have undergone.

1972 Jones’s spiritual autobiography, The Knee of Listening , was first published. Jones began formal teaching.

1973 Jones announced his first name change, becoming Bubba Free John, and began “crazy wisdom” teaching.

1974 Jones proclaimed himself an avatar (incarnation) of God.

1983 Jones acquired Naitauba, a private several-thousand acre island in Fiji previously owned by television actor Raymond Burr.

1985 A series of critical, lurid newspaper exposés of Jones appeared, leading to negative national press and television coverage of Adidam.

2008 (27 November) Jones (now Ruchira Avatar Adi Da Samraj) died at age sixty nine in Fiji.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Franklin Jones is the founder, guru, and primary focus of the new religious movemen t known as Adidam. Adidam revolves around Jones who, though now deceased, claimed to be completely enlightened, God in human form, and eternally present as the divine truth and source of awakening for all humanity. Not surprisingly, his biography is central to the history of the group.

t known as Adidam. Adidam revolves around Jones who, though now deceased, claimed to be completely enlightened, God in human form, and eternally present as the divine truth and source of awakening for all humanity. Not surprisingly, his biography is central to the history of the group.

In the hagiographic account of his life, Jones stated that he was born conscious and fully enlightened in 1939; his early life was an “ordeal” during which he gradually surrendered his blissful, enlightened state in order to live as an ordinary human. In the multiple editions of The Knee of Listening, his self-mythologizing autobiography, he claimed to have spent the next three decades working to recapture the spiritual “brightness” that was his original nature. Jones taught that this unrestrained, free, prior, bright, enlightened state of mindless, unconditional happiness is the fundamental nature of all humans. However, through the years he made varying, and growing, claims for the uniqueness of his own exalted state. In 1974, he announced that he was an “avatar,” an incarnation of God in human form. By the end of his life, he was asserting that he was, “the First and the Last and the Only seventh stage Adept (or Maha-Jnana-Siddha Guru) to Appear in the human domain (and in the Cosmic Domain of all and All)” (Adi Da Samraj, n.d.). (The non-standard capitalization is characteristic of Jones’ later prose.) In contrast to many spiritual teachers who are revered as avatars by their disciples, Jones seemed to be claiming a more exalted status than that of a simple incarnation of God. Jones proclaimed himself to be the first, last, and only being of his uniquely divine stature ever to arise anywhere.

Throughout his career as a guru, Franklin Jones repeatedly created or was given new names, including Bubba Free John, Da Free John, Da Love-Ananda, Dau Loloma , Da Kalki , Da Avadhoota , Da Avabhasa, the Ruchira Avatar, Parama-Sapta-Na, finally ending with Ruchira Avatar Adi Da Samraj, though several of the earlier epithets are still used in addition to Adi Da Samraj. Many of these name changes were prompted by what Jones claimed to be dramatic evolutionary developments in his already fully realized, divine condition. For the sake of narrative continuity, Franklin Jones will be referred to here as either Jones or Da.

The development of his spiritual career is well documented. It begins with an apparently normal childhood. His parents were middle class, though not much is written about them in Jones’s work. (In fact, readers of the later editions of Knee learn more about Robert, a cat that Jones describes as his “best friend and mentor,” than they do his family (Adi Da 1995:131). Jones excelled in school, earning degrees from Columbia and Stanford Universities. After obtaining a master’s degree in English from Stanford, he struggled to find himself, avoiding work, reading extensively, and experimenting with drugs, introspective writing and other self-invented exercises that he hoped would reveal the nature of consciousness. He spent several years in California as a near recluse engaged in intensive introspection and spiritual experimentation. His goal all along, he states, was to recover the “Bright,” the spiritually illumined state of his infancy. Eventually, he reported seeing visions of an Asian art store that he sensed was in New York City. He was sure that he would find his teacher there.

Jones and his long-term girlfriend Nina, later his first wife, moved across the country to New York in 1964 and soon located the store in Jones’s visions. There Jones encountered Rudi (Albert Rudolph, 1928-1973), also known as Swami Rudrananda. Rudi  evidently saw Jones as undisciplined and lazy; Rudi refused to teach Jones until he had a job and cleaned up his life. Jones reported that he willingly remade himself at Rudi’s command, for he believed that Rudi could transmit a tangible, transforming spiritual energy. Rudi called this energy “the Force.” (This occurred years before George Lucas employed the term in his Star Wars movies.) The transmission of spiritual energy (called Shakti in Sanskrit) and an emphasis on disciplined work would later become prominent features of Jones’s own teaching method.

evidently saw Jones as undisciplined and lazy; Rudi refused to teach Jones until he had a job and cleaned up his life. Jones reported that he willingly remade himself at Rudi’s command, for he believed that Rudi could transmit a tangible, transforming spiritual energy. Rudi called this energy “the Force.” (This occurred years before George Lucas employed the term in his Star Wars movies.) The transmission of spiritual energy (called Shakti in Sanskrit) and an emphasis on disciplined work would later become prominent features of Jones’s own teaching method.

After several years with Rudi, Jones began to feel that he had reached a spiritual dead end. He had met all of Rudi’s demands, including the unpleasant requirement that he study at a Lutheran seminary. Though the seminary experience was cut short, by what Jones describes as either a bad anxiety attack or a spiritual breakthrough (Jones 1973a: 60-63), Jones’s theological sophistication presumably received a boost from the education he received. While he had learned a great deal during his years with Rudi, he decided he was no closer to the permanent, effortless state of ecstasy he sought. Rudi’s path required unremitting spiritual work.

Against Rudi’s advice, Jones then decided to go to India to meet Swami Muktananda (aka Baba Muktananda, 1908-1982), Rudi’s guru. Over the course of several trips to India, Jones reported having a number of profound spiritual illuminations. He eventuallyasked Swami Muktananda for a letter confirming his (Jones’) realization. The one-page letter Jones received was hand-written in Hindi and has been retranslated and annotated a number of times. In its later versions, it reads as if Jones simply wrote it himself. Whatever its original content, the letter is often cited to prove that Jones’s spiritual realization was recognized within an established Indian guru lineage.

Throughout his teaching career, Jones struggled to demonstrate the legitimacy of his enlightenment. On one hand, he claimed to have gone far beyond every spiritual teacher who had ever lived; his realization was greater, more complete, and beyond comparison with anyone else’s. His enlightenment exceeded that of Muktananda, Ramana Maharshi (1879-1950), Jesus, the Buddha, and every other sage known to history. He needed no endorsement from anyone. On the other, he spent a great deal of effort trying to demonstrate that Swami Muktananda, a deeply flawed guru by many accounts (see Rodamore n.d.), had authorized him to teach. This is just one of several paradoxes to be seen in Jones’s life story.

In between his trips to India to be with Muktananda, Jones took a year off to practice Scientology , receiving extensive auditing and working full time for the organization. The chapter of Knee that deals with Scientology is found only in the first edition, though it was posted for a while at “The Beezone,” an independent but generally pro-Adidam Internet site. It does not appear to be available on the Internet at present. In that chapter, Jones described how his initial interest in Scientology faded when he discovered that its methods only address the contents of the mind, not the fundamental problems of consciousness. Jones also critiqued L. Ron Hubbard, the founder of Scientology, claiming that Hubbard was interested only in power, not wisdom or spiritual freedom. Nonetheless, Jones reports having made extraordinary progress in auditing, reaching “Clear” and passing through several O.T. (Operating Thetan) levels in just one year. (Jones is vague when describing his progress through Scientology’s O.T. levels, so it is unclear exactly how far he went.)

, receiving extensive auditing and working full time for the organization. The chapter of Knee that deals with Scientology is found only in the first edition, though it was posted for a while at “The Beezone,” an independent but generally pro-Adidam Internet site. It does not appear to be available on the Internet at present. In that chapter, Jones described how his initial interest in Scientology faded when he discovered that its methods only address the contents of the mind, not the fundamental problems of consciousness. Jones also critiqued L. Ron Hubbard, the founder of Scientology, claiming that Hubbard was interested only in power, not wisdom or spiritual freedom. Nonetheless, Jones reports having made extraordinary progress in auditing, reaching “Clear” and passing through several O.T. (Operating Thetan) levels in just one year. (Jones is vague when describing his progress through Scientology’s O.T. levels, so it is unclear exactly how far he went.)

In May of 1970, Jones returned to India with Nina, now his wife, and Pat Morley, a female friend, but was dissatisfied with his reception and experiences at Muktananda’s ashram. One day at the ashram, Jones experienced a vision of the Virgin Mary that sent the three of them on a pilgrimage to holy sites in Israel and Europe.

By August of 1970, the three were living together in Los Angeles, while Jones meditated full time. In September of that year, he claims to have experienced complete, permanent enlightenment in the Hollywood Temple of the Vedanta Society. Here is how he described the experience (or, more properly, non-experience) in the temple: “I simply sat there and knew what I am… I am Reality, the Self, and Nature and Support of all things and all beings. I am the One Being, known as God, Brahman, Atman, the One Mind, the Self” (Jones 1973a:134-35). Jones spent the next few years integrating his insights with his reading, slowly drawing informal followers and preparing for his public teaching work.

In 1972, Jones began teaching in a meeting hall at the back of Ashram Books (later Dawn Horse Books), the spiritual bookshop he and a few friends had recently opened in Los Angeles. By this point, Jones was functioning as an independent guru and developing his own methods. He had broken with both Rudi and Muktananda, believing that neither understood his true spiritual stature and that neither came close to his degree of realization. (Jones reestablished contact with Rudi, before the latter’s death in 1973, but grew increasingly critical of Baba Muktananda, while still recognizing Baba’s crucial role in the rediscovery of his original divine state.)

Even before his realization in the Hollywood Temple, Jones had developed a reputation for the ability to trigger spiritual experiences in others. This transmission became a marker of his early teaching work and made him stand out from the growing number of gurus and teachers appealing to America’s spiritual counterculture. He was also articulate, funny, extremely self-confident, and relatively young, which added to his appeal. He seemed to know a great deal about meditation and consciousness that could not readily be learned from the books available at that time (Lowe and Lane 1996).

Jones’ first book, The Knee of Listening , came out in 1972 and was well received by its target readership. The foreword by Alan Watts, a highly revered author and speaker, conferred instant respectability on Jones within the counterculture. Curiously, Watts’ admiration was based entirely on the persuasive power of Jones’ writing; the two men never met in person. This was the beginning of a pattern. Through the years, a number of admirers endorsed Jones’ great spiritual realization based almost exclusively on his written texts.

a pattern. Through the years, a number of admirers endorsed Jones’ great spiritual realization based almost exclusively on his written texts.

Very quickly, Jones began expressing frustration with his students’ lack of preparation for real spiritual work. In response, he began setting conditions and requirements for his early following. After 1972, Jones was increasingly sheltered from casual contact with ordinary people. Only devotees who had passed through prescribed coursework and lifestyle disciplines were allowed to see him, and then only in tightly controlled circumstances. For the rest of his life, he lived a highly sheltered existence within his community’s ever increasing number of properties, and even celebrity supporters of his work were rarely allowed into his presence. As far as can be determined, he was never interviewed by a journalist or other non-devotee, and he never engaged in public debate, or even conversation, with other spiritual teachers in the United States. He had no peers.

In 1973, after another trip to India, Jones announced the first of many name changes; he was now to be addressed as Bubba Free John. He also moved the center of his growing movement to Northern California. His rank and file followers settled in the Bay Area, while Jones and his entourage moved to a ramshackle hot-springs resort called Seigler Springs, but soon rechristened “Persimmon.” On weekends, devotees drove up from the Bay Area to Persimmon, working vigorously to transform the decrepit resort into an aesthetically pleasing retreat center. While at Persimmon, Jones’s teaching took a dramatic turn.

Jones, now called Bubba Free John, inaugurated a period of experimentation during which weeks of wild partying and antinomian rule breaking would alternate with weeks of rigorous self-control, fasting, and spiritual discipline. His devotees never knew what to expect, as Jones orchestrated the changes in his community with absolute control and inscrutable timing. While directing his community in its bacchanalian revels, Jones asserted that he was teaching them to see the nature of their own carnal and materialistic desires. He claimed that what he did was not based on his own cravings but was merely a skillful response to theirs; his role as guru was to serve as a pure mirror reflecting the unhealthy attachments of his devotees.

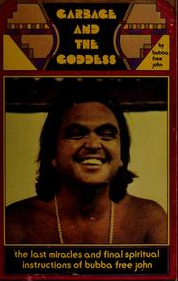

Garbage and the Goddess, a book of collected talks from this period of his teaching, depicts a community enthralled and excited by  miraculous experiences and the prospects of rapid spiritual growth. Soon after the publication of Garbage , the Dawn Horse Press, Jones’s self-publishing organ, attempted to recall and burn all copies of the text (Kripal 2005). Evidently, someone decided that the “crazy wisdom” actions recounted in the text were too frank for popular consumption.

miraculous experiences and the prospects of rapid spiritual growth. Soon after the publication of Garbage , the Dawn Horse Press, Jones’s self-publishing organ, attempted to recall and burn all copies of the text (Kripal 2005). Evidently, someone decided that the “crazy wisdom” actions recounted in the text were too frank for popular consumption.

In 1979, Jones declared, “Beloved, I Am Da” (Lee 1998:339), and subsequently took the name Da Free John, inaugurating a series of names that incorporate the syllable Da. According to Jones, Da is an ancient word in several languages meaning “the Giver.” (It can mean that in Sanskrit.) His teachings continued to evolve, along with his names and titles.

For the next decades, Da alternated periods of teaching with times of seclusion, writing, and making art. Meanwhile, the majority of his devotees lived in or near Adidam communities, mostly in the United States, Europe and Australia, following his detailed spiritual instructions, working full time jobs, and struggling to attract more followers.

Despite Da’s prolific writing and extensive publishing efforts , his community grew slowly and from most accounts never expanded much beyond 1,000 committed members at any time, though perhaps 20,000 or so spiritual seekers have been involved at least briefly with his organization over the last forty years. One reason for the relatively modest size of Da’s following, as compared, say, to that of Muktananda or Ammachi (1952- ), might be found in Da’s personal refusal to participate in public outreach. Others include the increasingly unconventional way he presented himself in official Adidam photographs and the growing eccentricity of his prose.

Potential devotees had to come to him and prove their devotion over a period of months, taking courses, tithing (often twenty percent of earnings), and engaging in service to his organization, before they could earn their first sitting in his presence. This trial period guaranteed that new followers would be appropriately screened and socialized before seeing the guru; it also ensured that fledgling devotees would be in a state of high anticipation when they finally were allowed to see Da. This expectation presumably intensified their first experience of the guru and his reputed shakti , or spiritual energy. The downside, of course, is that only a relatively few individuals were willing to invest the requisite time, money, and effort in advance of receiving a possible, but uncertain, spiritual payoff.

Da’s increasingly strange prose also discouraged potential followers. Curious readers opening one of Da’s books in a shop would immediately encounter oddly worded and punctuated texts that could be quite challenging. The sales figures for Da’s later works are low. Although Da had been an engaging, entertaining speaker back in the 1970s, his later works are extremely dense. The net result is that his organization was set up in a way that discouraged expansion, despite Da’s stated desire to bring the entire world to his feet. He called himself “The World-Teacher,” so the failure of his small, numerically stable following to grow frustrated him greatly (“Adi Da Discusses the Failures of the Last 30 Years” 2001).

An elaborate set of rules and regulations were created for Da’s devotees, who were divided into three hierarchical congregations based on their length of time in the religion, their academic understanding of Da’s teachings, their spiritual “maturity,” and their financial commitment. (A fourth congregation for traditional and indigenous peoples has since been established.) Da and his entourage were supported, in part, by the sale of books and magazines produced by devotees at the Dawn Horse Press, but their primary source of income was tithes and contributions solicited from followers. From all reports, Da and his extended household needed a great deal of money to maintain their opulent lifestyle, so the hardworking rank-and-file devotees were often pressed for cash.

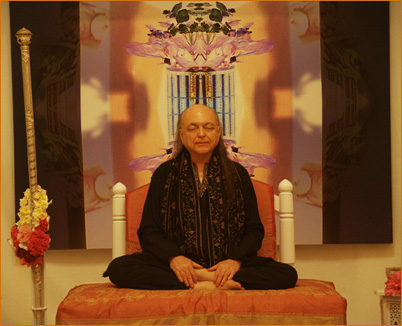

In his last years, Da spent a great deal of time in Fiji working on his photographic art and taking steps to establish a spiritual legacyto withstand the ages. He claimed that his photography was not frivolous or self-indulgent entertainment, but a form of spiritual expression; the multiple images he assembled in his massive collages provide a window into liberation (“Transcendental Realism” 2013).

last years, Da spent a great deal of time in Fiji working on his photographic art and taking steps to establish a spiritual legacyto withstand the ages. He claimed that his photography was not frivolous or self-indulgent entertainment, but a form of spiritual expression; the multiple images he assembled in his massive collages provide a window into liberation (“Transcendental Realism” 2013).

He continued to write prolifically and published an enormous amount, claiming “perpetual copyright” for his works and any others produced by his community, to ensure their faithful preservation. This is probably not a good thing for his literary legacy, because the most recent editions of his first books are far less engaging and much harder to read than the earlier, now unofficial, versions.

At one point, Da planned to create “living murtis” to continue his spiritual blessing after his physical death. The Sanskrit word murti means consecrated image and is used in India to refer to statues and paintings of deities. Da’s living murtis were to be human beings who would somehow be emptied of their own individuality, in order to be filled with Da’s energy which they would then be able to transmit. It sounded as if they were to function like impersonal human spirit batteries, filled with the divine current of Da. This plan was dropped without fanfare in favor of creating spiritually empowered sites. Da subsequently meditated and conducted rituals to empower sacred shrines at each of Adidam’s sanctuaries. The sacred shrines will contain their ability to transmit Da’s divine awakening energy for millennia, as long as they are not profaned by spiritually insensitive or unprepared visitors. Apparently, devotees believe that sightseers with negative attitudes can destroy the blessing power of the shrines.

On 27 November 2008, while working on his photography in his Fijian sanctuary, Da fell over dead from a massive heart attack. When it became clear that he was not going to resurrect, despite the hopes of his inner circle, his body was enshrined in a tomb he had designed years before. Da’s tomb (mahasamadhi in Sanskrit) on the island of Naitauba is now regarded by followers of Adidam as the most important spiritual power point in the world. Devotees believe that Da is still present and acting in the world—not as a personality, but as divine energy and light. Somewhat surprisingly, given his huge literary output and colorful lifestyle, Da’s public profile, in life and death, remains low.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Chronicling the evolution of Jones’ spiritual teachings and core beliefs is a fascinating challenge. Part of the difficulty in evaluating Da comes from the profusion of sources. He published at least seventy separate books during his lifetime, twenty-three of which he designated as “source texts.” (Ranker.com lists 147 titles, though some of these “books” appear to be excerpts drawn from longer works.) Many of Jones’ major texts are lengthy and have been released in multiple editions that vary considerably in content. This is especially evident in The Knee of Listening , which grew enormously and shows extensive revision in later editions. In the last decades of his life, Jones published “New Standard Editions” of a number of his works, in an effort to preserve his teachings for posterity in a fixed, final, authoritative form. (While scholars sometimes produce new standard editions of ancient texts, like the Bible, that are compiled over centuries by many redactors, it is rare for a writer to create them for his own self-published works.)

When Jones began teaching in 1972, his basic cosmology seemed broadly drawn from Vedanta, the related system of Kashmiri Shaivism, and the teachings of Swami Muktananda. Though he claims that his teachings are universal, neither Eastern nor Western, their strong Vedantic-Hindu roots are clearly revealed in his belief system and spiritual practices. Hindu-derived teachings like karma, rebirth, spiritual liberation, guru devotion, and a host of other South Asian beliefs and practices are simply taken for granted and assumed to be true. Jones taught that the individual Self is by its very nature divine, blissful, and eternal. The individual Self, or Atman, is in fact none other than Brahman, or God. Humans fail to experience their already present divine condition due to a universal process of self-contraction and self-reflection, which leads them on an endless search for that which is already their true nature. Jones identifies this search with the Greek myth of Narcissus, the god so enamored with his reflection that he became lost in contemplation of his own image. The Truth, Jones claims, is prior to thought and self-reflection. Although it is always already there, one must undergo a complete transformation to make it a living reality.

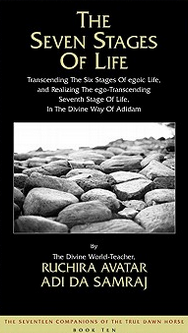

Perhaps the most influential of Da’s intellectual innovations is his theory of the seven stages of life. Though Da might have been inspired by the theories of Erik Erikson and Jean Piaget, he certainly developed his stages in ways neither of his forerunners could have anticipated. As Da explained at considerable length, the first three stages describe ordinary psychological and physical development. Although a human should master these three by the time they finish school, most humans never mature beyond them. The fourth and fifth stages are where real spiritual growth begins; this is where Da placed most of his rivals, past, present and future. The sixth is the state of perfect realization of consciousness-only, while the realizer remains oblivious to the external world. This is the furthest anyone, before Da, had ever gone. The seventh is the unique state of Da, one in which both perfect, unbounded consciousness and the physical world are completely, effortlessly realized. One in this state enjoys sahaja samadhi , the bliss of complete open-eyed ecstatic awareness, while in the midst of any and all activities.

inspired by the theories of Erik Erikson and Jean Piaget, he certainly developed his stages in ways neither of his forerunners could have anticipated. As Da explained at considerable length, the first three stages describe ordinary psychological and physical development. Although a human should master these three by the time they finish school, most humans never mature beyond them. The fourth and fifth stages are where real spiritual growth begins; this is where Da placed most of his rivals, past, present and future. The sixth is the state of perfect realization of consciousness-only, while the realizer remains oblivious to the external world. This is the furthest anyone, before Da, had ever gone. The seventh is the unique state of Da, one in which both perfect, unbounded consciousness and the physical world are completely, effortlessly realized. One in this state enjoys sahaja samadhi , the bliss of complete open-eyed ecstatic awareness, while in the midst of any and all activities.

By the time the first edition of Knee was published, Jones claimed that he no longer meditated for himself but rather meditated other people, some familiar to him and others unknown. This process of “meditating other people” seems to be the basis of his later “blessing work,” in which he claimed to meditate countless beings. According to the reports of his devotees, Jones was able to effect changes in the consciousness of others through his unusual siddhi, or spiritual power.

RITUAL/PRACTICES

By 1972, Da was experimenting with his followers, enjoining a strict vegetarian diet, with an emphasis on raw foods, fasting, enemas, hatha yoga, and other body practices that he hoped would make his devotees more receptive to the spiritual energies he was radiating. In his earliest instructions, Jones taught devotees to meditate daily before his photograph, asking themselves “Avoiding relationship?” This seems similar to the process of spiritual inquiry, using the question “Who am I,” that was advocated by Ramana Maharishi as a method of cutting through to the core of Being. Jones also placed great emphasis on satsang , group meetings in which devotees sit in the presence of the master. Adidam’s websites contain many accounts of the powerful spiritual experiences that devotees reported in Jones’s presence (“Personal Testimonials of Avatar Adi Da Samraj’s Devotees” 2008).

From this simple beginning, Adidam grew into a complex and complete lifestyle. Fully committed devotees still follow all the early practices, but in addition they practice various tantric sexual disciplines, conduct Hindu-style pujas and aratis (formal worship rituals with offerings), memorize chants and sacred texts, read Da’s works daily, tithe, engage in service to the organization, take an “eternal vow” binding them to Da, and go on pilgrimage to the sacred empowered sites of the faith. Adidam has become a complex, mature religion, with a ritual/liturgical calendar, sacred celebrations, a voluminous sacred literature, and more than enough requirements to keep devotees busy for several lifetimes.

Da often placed extraordinary demands on his devotees, especially in the early years of his movement, which he justified as a form of “crazy wisdom” teaching. Da claimed that any authentic guru capable of employing crazy wisdom methods must necessarily have transcended all fixed moral codes. He was therefore free to use any shock tactic, no matter how conventionally immoral or offensive, in order to wake his devotees from their spiritual sleep. Da dissolved his devotees’ established marriages, assigned new partners, required devotees to drink alcohol, strip naked, be filmed having sex, and to engage in other, even more transgressive behaviors, behaviors that triggered strong aversion in nearly everyone involved. Whatever he was trying to accomplish, it is clear that he was effective at convincing his devotees that they were participating in a great, if traumatic, spiritual adventure .

As Da’s teachings evolved, bhakti, or devotional worship, eventually supplanted spiritual inquiry as the preferred method of transformation for followers of Adidam. Da evidently decided that his devotees might best escape their own obsessive, narcissistic self-contemplation by directing all their attention onto him. Rather than allow their minds to wander, distracted by the petty concerns and mundane insights of normal thought, his devotees should focus their hearts, bodies, and minds on the physical form of their guru, the “World-Teacher” and Ruchira Avatar, and thereby become absorbed in his Divine Reality. Though this sounds very much like standard Hindu guru devotion, Da calls this process “Ruchira Avatar Bhakti Yoga” and claims it as a unique revelation. Here is how he explains the yoga:

If you understand the “self”-contraction (and all seeking) “Radically” (or “At The Root”) by Means of My Teaching-Argument, then you are in the disposition that can be Acausally Enabled (by Means of My Divine Avataric Transcendental Spiritual Grace) to be Self-Established In and As That Which Is Prior to the “self”-contraction, or That in The Context of Which the “self”-contraction is arising. Therefore, “Radical” (or “At-The-Root”) “self”-understanding, Directly Enabled by Means of My Teaching-Argument, allows you to begin the Real (devotionally Me-recognizing and devotionally to-Me-responding) practice of The only-by-Me Revealed and Given Seventh Stage Reality-Way of Adidam (Adi Da 2009).

Ruchira Avatar Bhakti Yoga places extraordinary emphasis on Da’s body. It is not seen as a simple human form of flesh and bone but as a full expression of divinity, or “Real God” as Da puts it. Da’s body was not always so extraordinarily divine, in fact his spirit was once largely dissociated from his flesh, but after one of his dramatic near-death revelatory experiences, Da claimed that the divine had descended fully into his physical form, which made it the perfect object for his devotee’s contemplation. Now that Da is dead, his tomb site in Fiji and his other empowered sanctuaries are seen as uniquely powerful devotional sites for followers of Adidam.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

The religion/community Da established has been known by many names, including Shree Hridayam Satsang, The Dawn Horse Communion, The Free Primitive Church of Divine Communion, The Crazy Wisdom Fellowship, The Johannine Daist Communion, The Advaitayana Buddhist Communion, The Eleutherian Pan-Communion of Adidam, and more. Da clearly enjoyed playing with names. Now it is usually simply called Adidam, and followers are “Daists.”

Over time, Da acquired a number of “sanctuaries,” in addition to Persimmon (now called The Mountain of Attention Sanctuary). The most important of these is the Fijian island of Naitauba, which his movement acquired in 1985. Another is on Kauai. There is also a sanctuary in Washington State and a second sanctuary in Northern California. Based on pictures available on the Internet, all of these properties appear beautifully landscaped, with elegant shrines and temples. Unfortunately, admission to the sanctuaries is highly restricted; due to their spiritual fragility the inner areas are open only to advanced devotees. (“Visiting the Sanctuaries of Adidam” n.d.) Even while on retreat in his sanctuaries, Da was usually surrounded by a loyal inner circle, including a changing roster of multiple “wives” and “intimates.”

During his life, Da was widely believed to micromanage his entire empire with an iron hand, though officially he owned nothing and Adidam’s resources were administered by a trust. Given that all the trustees were devotees who believed that Da was the “Ruchira Avatar,” “Real-God,” and the “World-Teacher,” it would be quite odd if they did not follow his instructions faithfully. Defectors from the inner circle have said that this was, of course, the case. Now that Da is gone, the trustees presumably have real power, but the administration of the movement remains opaque.

Da made great efforts to insure that his religion would continue after his death exactly as he had established it, but it is unclear how well this will work in reality since all religions evolve. As an astute student of religion, Da must have known that. Evidently, he thought that his religion would be the exception to the rule. Da made certain, as best he could, that he would never be supplanted by a human guru—he was the first, last and only seventh stage realizer—but even this may be challenged at some future point. So far, at least from an outsider’s perspective, the religion appears to be holding on; if there are leadership struggles, they are not visible to the public.

Perhaps in recognition of the fact that only small numbers of devotees have been drawn to the faith, Adidam is now divided into four congregations of decreasing strictness. The first is truly high demand and comprises the most committed and intense practitioners of Da’s spiritual discipline. The second congregation is still fairly demanding, but includes students with less advanced understanding and perhaps less complete devotion. The third is for those who feel devotion for Da and contribute money, but who are not ready for the disciplinary requirements of the faith. Members of the third congregation are still permitted to participate in other religious traditions. The fourth is perhaps the most unusual. It is composed exclusively of indigenous peoples (Fijians mostly?) who feel devotion for Da but are otherwise uninvolved in the organized religion he has created.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Franklin Jones began his career in the 1970s as a young, uninhibited, charismatic, humorous, exuberantly self-confident guru. However, Jones and his movement faced a continuing series of challenges, including his radical teaching practices, his charismatic claims, and the future of his movement following his death.

Jones drew high praise for his thought from a number of notables. These supporters find Da’s vast corpus of texts to be “encyclopedic” and inspiringly complete. Religious Studies professor Jeffrey Kripal wrote in the Foreword to The Knee of Listening, “ From the day I first encountered the writings of Adi Da (as Da Free John) in the mid-80s, I knew that I was reading a contemporary religious genius.” As popular author Ken Wilber puts it, “Adi Da’s teaching is, I believe, unsurpassed by that of any other spiritual Hero, of any period, of any place, or any time, of any persuasion” (Wilber 1995).

As discussed above, Jones adopted the term “crazy wisdom” to describe his teaching during the mid-1970s, and his supporters have justified his extreme behaviors on that basis. Jones’ defenders often claim that Jones was not innovating so much as reviving ancient traditions of crazy wisdom teaching; however, scholars disagree whether there has ever been anything that could be recognized as a crazy wisdom tradition, though there have certainly been crazy-wise teachers. Even if such a tradition existed it is not clear that Jones’ behavior would fit within it (Feuerstein 1991).

Whatever the status of Jones’ thought and the crazy wisdom teachings, the biggest challenge Adidam has faced, from as early as 1973, is the radical practices associated with those teachings. Jones and his devotees have published numerous accounts of Da’s spiritual power and their transformative metaphysical effects on followers. From a believer stance, because Jones was a supremely enlightened being, any action he took was spontaneously right and beneficial for his devotees; their immediate pain would lead to great liberation in the future. Since, from a cosmic perspective, spiritual liberation is the only thing that matters, then how one is led there is secondary. The true guru uses what works.

At the same time, there has been a series of scathing exposes written by disillusioned ex-disciples that depict Jones as a brilliant manipulator and powerful transmitter of energy (shakti, in Sanskrit) who used his charismatic authority to exploit, abuse, and humiliate his devotees (See, for example, Chamberlain, “Beware of the God” n.d.). His harshest critics argue that Jones was a slick sociopath who enjoyed humiliating and debasing his followers (See, for example, Conway 2007). Some former members, despite their rejection of Da and his methods, have nonetheless continued to believe that Da possessed a mysterious power to induce experiences of bliss and insight in responsive individuals. One major argument put forward by former members to support their allegations of exploitation is that during the “Garbage and the Goddess” period, when radical practices were at their height, it was claimed that Jones himself was adhering to the same disciplines as his followers. However, former members have amassed evidence demonstrating that for the rest of his life Da secretly continued to drink, take drugs, have promiscuous sex, and violate the dietary restrictions required of his devotees (Lowe 1996, 2005; Chamberlain 1996; Feuerstein 1991). From Da’s perspective, of course, this was simply part of his spiritual teaching mandate: “What I do is not the way that I am, but the way that I teach” (Bubba Free John 1978:53).

A second issue was Da’s charismatic claims, which certainly must have been offensive to other spiritual leaders. He made truly extraordinary claims for himself that some found extremely narcissistic.

“Those who Do Not heart-Recognize Me and heart-Respond to Me – and who (Therefore) Are Without Faith In Me — Do Not (and Cannot) Realize Me. Therefore, they (By Means Of their own self-Contraction From Me) Remain ego-Bound To The Realm Of Cosmic Nature, and To The Ever-Changing Round Of conditional knowledge and temporary experience, and To The Ceaselessly Repetitive Cycles Of birth and search and loss and death. Such Faithless beings Cannot Be Distracted By Me — Because they Are Entirely Distracted By themselves! They Are Like Narcissus — The Myth Of ego — At His Pond. Their Merely self-Reflecting minds Are Like a mirror in a dead man’s hand ( Adi Da Samraj 2003: 77-78 ).

These claims were coupled with others that directly or indirectly denigrated the spiritual status of his competitors. For example, it might be argued that Da’s model of seven stages of spiritual development was perhaps his most important intellectual contribution. However, he changed the rules of classification over time in a way that lowered the status of other teachers. Ramana Maharshi, once a full seventh-stage realizer, was later demoted to the sixth stage. Jesus, the Buddha, and others were also downgraded over time to fourth and fifth stage status. Rather than serving as a roadmap to higher consciousness, the seven stages functioned mostly as a means for Da to denigrate rivals.

Of course, from the position of Da and his supporters, he was not speaking as a limited human individual but from the stance of the divine. Any narcissism that observers thought they saw in Da was simply a reflection of their own narcissism, or perhaps an indication of their undeveloped understanding and lack of spiritual development. (See “ The Three Cards ‘Mindfuck’ Trick” n.d.)

Finally, Adidam has faced the challenge of its future survival. Will the institutions, empowered sanctuaries, courses, websites, rituals, devotional practices, meditation methods, and books be enough to keep the tradition vital, or will Adidam, like so many other new religions of the past, dwindle with its aging congregations? Da himself lamented that his work had not been successful. Despite all his writing, building, teaching, confrontational “theatre,” social experimentation, artistic creation, and world blessing, he left behind no enlightened devotees. This situation may change slightly as one of his female “intimates” reportedly meditates full time at Da’s burial site and is in an advanced stage of realization in Fiji. Da also often dismissed the value of other spiritual teachers by stating that “Dead gurus can’t kick ass!” (Jones 1973b:225). The implication was that only a living, breathing, confrontational guru could inspire, or coerce, followers to make the huge sacrifices needed to attain liberation. Only a living guru could “meditate them.” Once Da passed away, of course, he joined their ranks, although Adidam has attempted to reinterpret his remarks (See “Adidam in Perpetuity.”). It may well be the case that Adidam will survive to the extent that devotees continue to feel Da’s spiritual energy and believe that they are transformed by it.

REFERENCES

Adi Da (The Da Avatar). 1995. The Knee of Listening: The Early-Life Ordeal and the Radical Spiritual Realization of the Divine World-Teacher. New Standard Edition. Middletown, CA: The Dawn Horse Press.

Adi Da Samraj. N.d. “The Teaching, Demonstration, and Realization of Ramana Maharshi.” Accessed from “The Beezone” http://www.beezone.com/Ramana/Ramana_Teaching.html on 20 July 2013 .

Adi Da Samraj, the Ruchira Avatar. 2003. Aham Da Asmi (Beloved, I Am Da, 3 rd ed.) Middletown, CA: The Dawn Horse Press.

Adi Da Samraj, the Ruchira Avatar. 2009. “ The Seventh Stage Reality-Way Of No Stages At All.” The Aletheon . Excerpted in “The Beezone” accessed from http://www.beezone.com/AdiDa/Aletheon/the_seventh_stage_of_no_stage.html on 1 July 2013.

“Adi Da discusses the failures of the last 30 years.” Assessed from http://lightmind.com/library/daismfiles/failures.html reached through use of the Internet Wayback Machine on 21 May 2013. This was once archived on the Daism Research Index website, but that essential resource has been removed from the Internet.

“Adidam in Perpetuity.” Accessed from http://www.adidaupclose.org/Adidam_In_Perpetuity/ on 20 July 2013.

Butler, Katy. 1985. “Sex Slave Sues Guru: Pacific Isle Orgies Charged.” San Francisco Chronicle , April 4.

Chamberlain, Jim . 1996. “Beware of the God.” Accessed from http://bewareofthegod.blogspot.com on July 11, 2013.

Conway, Timothy. 2007. “ Adi Da and His Voracious, Abusive Personality Cult.” Accessed from http://www.enlightened-spirituality.org/Da_and_his_cult.html on 2 July 2013.

Feuerstein, Georg. 1991. Holy Madness: The Shock Tactics and Radical Teachings of Crazy-Wise Adepts, Holy Fools, and Rascal Gurus. New York: Paragon House.

Free John, Bubba. 1974. Garbage and the Goddess: The Last Miracles and Final Spiritual Instructions of Bubba Free John, edited by Sandy Bonder and Terry Patton. Lower Lake, CA: The Dawn Horse Press.

Free John, Bubba. 1978. The Enlightenment of the Whole Body . Middletown, CA: The Dawn Horse Press.

Goldberg, Phillip. 2010. American Veda: From Emerson and the Beatles to Yoga and Meditation—How Indian Spirituality Changed the West. New York: Harmony Books.

Jones, Franklin. 1973a. The Knee of Listening (2 nd edition). Los Angeles, CA: The Dawn Horse Press.

Jones, Franklin. 1973b. The Method of the Siddhas. Los Angeles, CA: The Dawn Horse Press.

Kripal, Jeffrey J. 2005. “Riding the Dawn Horse: Adi Da and the Eros of Nonduality.” Pp. 193-217 inGurus In America, edited by Thomas Forsthoefel and Cynthia Ann Humes. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Lattin, Don. 1985. “Guru Hit by Sex Slave Suit.” San Francisco Examiner, April 3. Accessed from http://www.rickross.com/reference/adida/adida16.html on 11 July 2013.

Lee, Carolyn. 1998. THE PROMISED GOD-MAN IS HERE: The Extraordinary Life-Story, The “Crazy” Teaching Work, and The Divinely “Emerging” World-Blessing Work of The Divine World-Teacher of the “Late-Time”, RUCHIRA AVATAR ADI DA SAMRAJ. Middletown, CA: The Dawn Horse Press.

Lowe, Scott and Lane, David. 1996. Da: The Strange Case of Franklin Jones. Walnut, CA: Mt. San Antonio College Philosophy Group.

Lowe, Scott. 2006. “Adidam.” Pp. 85-109 in New and Alternative Religions in the U.S., volume 4, edited by Eugene V. Gallagher and William M. Ashcraft. Westport, CT: Praeger.

“Personal Testimonials of Avatar Adi Da Samraj’s Devotees.” 2008. Accessed from http://www.adidam.in/Testimonials.asp on 6 August 2008.

Ranker.com. “Adi Da Books List.” Accessed from http://www.ranker.com/list/adi-da-books-and-stories-and-written-works/reference?page=1 on 5 July 2013.

Rodamore, William. “The Secret Life of Swami Muktananda.” Accessed from http://www.leavingsiddhayoga.net/secret.htm on 10 July 2013.

“The Three Cards ‘Mindfuck’ Trick.” Accessed from http://www.kheper.net/topics/gurus/Three_Cards_Trick.html on 1 July 2013.

“Transcendental Realism: The Art of Adi Da Samraj.” 2013. Accessed from http://www.daplastique.com/art/index.html on 8 August 2013.

“Visiting the Sanctuaries of Adidam.” Accessed from http://www.adidaupclose.org/FAQs/visiting_sanctuaries.html on 16 July 2013.

Wilber, Ken. 1995. Jacket blurb on the back cover of the 1995 edition of The Knee of Listening . Wilber’s enthusiastic quotes can be found on the covers of many editions of Da’s books.

Post Date:

23 August 2013